The past, present, and future of inequality

There is a lot that is new – and scary – in our modern world. We have seen an accelerating onslaught of crises across global economic, environmental, and socio-political systems; what commentators refer to as a polycrisis. At the same time, as historians we are consistently struck by how much is eerily familiar. Our work at Societal Dynamics (SoDy), drawing on historical insights from the Seshat Databank project, gives us a panoramic view of familiar patterns that seem to be repeating themselves today.

One of the clearest patterns that jumps out is how truly insidious inequality has been throughout history. When differentiation in wealth, power, access, and privilege takes hold, they tend to perpetuate themselves. This causes the gap between the ‘haves’ and ’have nots’ (or the ‘have less-es’) to keep getting wider and wider from one generation to the next.

We observe this nearly everywhere we look across the historical record. From smaller-scale communities in the Southwest USA to ancient empires like Rome and Han China (Fig. 1) to the Caliphates that dominated Eurasia in the Middle Ages, and of course, to our current globalized world, we see similar patterns emerge time and time again.

Figure 1. ‘Terracotta Army’, over 8,000 statues of soldiers, chariots, and horses buried in the tomb of China’s Qin Dynasty emperor Shi Huang, meant to symbolically protect and serve him in the afterlife as he had been guarded in life. Image by chensiyuan under CC BY-SA 4.0 Licence |

The wealth pump

Our colleague Peter Turchin calls this process the “wealth pump” (Fig. 2)1: the all too common scenario where those with wealth and power set up social systems to essentially transfer more and more of their society’s wealth, assets, luxury goods, and other valuable commodities from the majority population to themselves.

The way this tends to happen is that certain groups gain positions of power – as political rulers, successful military leaders, holding some high religious position, or as wealthy landowners or manufacturers (and often, of course, the same people hold power in more than one domain). We call these people ‘elites’.

Figure 2. Rendering of a ‘Wealth Pump’. AI Generated image

These elites, because they hold disproportionate social power and influence, can – and typically do – use that power to reinforce their positions of privilege, allowing themselves and their children to gain even more wealth and power2. We see this clearly happening in the USA and many other contemporary countries3.

If allowed to go unchecked for a long period, this kind of inequality tends to snowball. One generation of ‘elites’ tweaks the rules to secure their own wealth and privileges, looking to leave their children as well-off or better than they were. Their children then bend the rules a little bit more as the competition for elite status continues to grow4. And so on.

Perhaps a better term for elites, then, is the ‘never-enoughs’, as this group tends to constantly seek out more and more wealth, status, and privilege, no matter how much they have already accumulated.

Sowing the seeds of crisis

When the wealth pump gets turned on and left to run for years or even generations, it rarely ends well – for anyone. Typically, when this kind of inequality is allowed to run amok for a long time, tensions build up until people have had enough. This includes the have-nots, but also the never-enoughs who tire of the constant struggle to keep up. Tensions can then boil over into some major crisis: a bloody civil war, assassinations of rulers, widespread unrest and violence, social systems failing, and sometimes even complete societal collapse.

The cycles experienced over the course of the millennium or so of Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean basin bear this pattern out well. Rome experienced recurrent periods of social unrest, civil war, and systemic shifts throughout its history, including the Conflict of the Orders, the 100 years of civil warfare at the fall of the Republic, the Crisis of the 3rd Century, and the eventual fall of Roman rule in Europe. The fighting and Rome’s expansionist policies were able to mollify tensions for long stretches, but because there were no concerted efforts to keep inequality at bay, after a while, Rome’s wealthy and powerful were able to turn the wealth pump back on, causing the cycle to restart once more.

Each of these crises was preceded by a prolonged period of rising inequality, even while the society might have seemed generally stable and generally on the ground. The 3rd Century Crisis notably came just a generation or two after the period which Edward Gibbon famously declared when “the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous”5.

Figure 3. Luxury in Bourbon France. ‘Hall of Mirrors’ in the Palais Versailles, Paris, France. Image by Dennis G. Jarvis under CC BY-SA 2.0Licence |

Other so-called 'golden ages,' like the Tang and Song Dynasties in China or Bourbon France (Fig. 3), are likewise lauded in modern history books for their flourishing economies and remarkable artistic achievements. But such eras usually turn out to be merely gilded, masking sharp inequalities while tensions build beneath the surface until they erupt into (another) bout of violence.

Turning Off the Wealth Pump

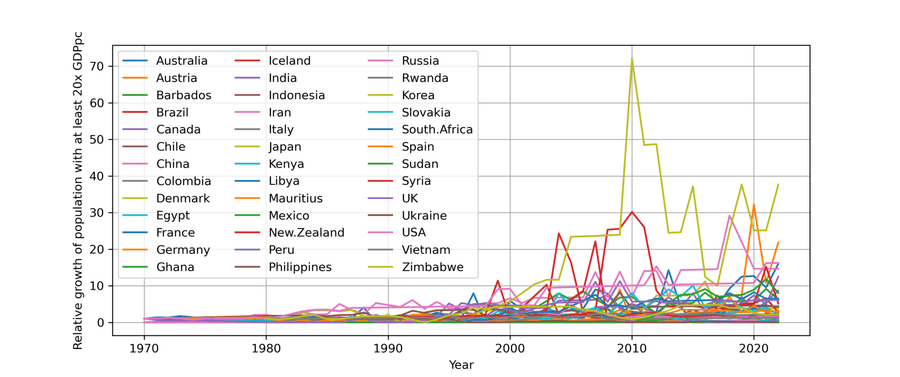

Figure 4. Relative growth in the percentage of the population across 41 countries with wealth at least 20 times greater than the GDP per capita (GDPpc) level between 1960 and 2024. While there are pronounced differences across countries, this illustrates the overall trend over time where wealth has been accumulating at the top and generating more and more ultra-wealthy citizens in a number of different contexts. Data from the World Inequality Database; calculations by the authors along with colleague James S. Bennett. |

By now, readers are likely noticing alarming parallels with many of our contemporary societies. Unfortunately, it seems like the wealth pump brought on by neoliberalist policies has been turned on almost anywhere you look around the world today, gaining momentum since the 1970s in many places6 (Fig. 4).

The scope and scale of our modern polycrisis only deepens this process. The rise of AI technology (the incredible profits to be made from it and its impact on surveillance and militarisation), our growth-obsessed and extraction-driven global capitalist economy, and the existential risks we are facing from climate change and biodiversity collapse themselves contributes to the inequity of billions of people around the world and continuing to pump wealth and power to a tiny cabal of global elites.

So what can be done? Well the obvious answer is that we need to turn off the wealth pump and reverse the rampant inequality we have allowed to build up. Thankfully, history provides just enough cases where societies accomplished this seemingly herculean task for us to retain some optimism.

The New Deal era in the USA is one of the clearest examples7. Labour reforms, banking regulations, fiscal changes, and major public works programs allowed the USA to experience a relatively robust, if gradual, recovery from the Depression compared to other countries; the suite of reforms was referred to collectively as the New Deal. It is not a coincidence that many efforts to transform economies towards more resilient, sustainable practices take the name of ‘green new deal’.

It is important to remember, though, that the original New Deal era was just that – it was an era of reform, not a single all-encompassing piece of legislation. And it would likely not have been possible, and certainly wouldn’t have been nearly as impactful, if not for the groundwork taken during the Progressive Era about a generation earlier.

The Progressive Era saw a series of policies put in place largely aimed at protecting industrial workers. These reforms only passed because some of the wealthiest elites of the time, ‘captains of industry’ like John Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Ford, saw the problems arising from the spiralling inequality they benefited from – and themselves had a big hand in creating. But working alongside President Theodore Roosevelt, they started to use their outsized social power to usher in changes that provided both immediate and lasting relief from some of the ills of America’s early industrial economy, and set the stage for the more expansive reforms in the 1930s8.

Giving Our Relationship to Wealth & Power a ReThink

The Progressive era and New Deal examples, along with similar moments of reform, offer something of a playbook for confronting the inequality we face today. This will not be an easy process that happens overnight; just as it has taken decades of decisions, policies, and reinforcement to get to this point, so too will it take a sustained effort of iterative, step-wise actions to relieve these pressures. And of course, we need to do this at the same time as we tackle the immediate needs of relieving economic disparities, slowing down global climate change, and the systemic violence that is causing real harm to (increasingly) unprotected groups.

But all hope is not lost. It has happened before and it can happen again now. To do this, though, we need to ReThink the patterns and behaviors that have led us to where we are today:

- We need to ReThink our economic and fiscal models, shifting from growth-at-all-costs to inclusive well-being models. We have enough for all of us, as long as we out our collective energies and wealth to supporting everyone, humans and non-humans alike .

- We need to ReThink our short-term focus and take action towards long-term, sustainable solutions while still meeting the urgent demands of today.

- We need to ReThink how we engage with ‘the other side’, bridging divides and generating broad buy-in for needed transformations rather than deepening our already polarized discourse and partisan hostility.

- We need to ReThink our relationship to power, addressing head-on the extreme disparities in wealth and social power we have allowed to grow over decades, recognizing that elite cooperation may be crucial for enacting true systemic change, as history shows that their opposition worsens the situation for everyone.

If we can do this, we might be able to establish new, better, more sustainable, and more just patterns in their place. And perhaps vanquish history’s great villain along the way.

For more on our work at SoDy, see our project site.

- A short informational video about our approach.

- A list of recent interviews, articles, and opinion pieces

- See more on the Seshat Databank project

Thanks for reading The Rethink series. All views expressed are the writer’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of ASRA. Stay connected and keep exploring — discover more Rethink pieces suggested below and under “View” on the Events & News page.

Footnotes

- Turchin develops this idea more substantially in his recent book: Turchin, Peter. End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites and the Path of Political Disintegration. London: Random House, 2023. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/447345/end-times-by-turchin-peter/9780141999296.

- Useful overviews of this general historical process are provided by e.g.: Wilkinson, Richard G, and Kate Pickett. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2011; Flannery, Kent, and Joyce Marcus. The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2012; Kohler, Timothy A, and Michael E Smith. Ten Thousand Years of Inequality: The Archaeology of Wealth Differences. University of Arizona Press, 2018; Saini, Angela. The Patriarchs: The Origins of Inequality. Beacon Press, 2023.

- Thomas Piketty and others make similar arguments, noting the general propensity for those with ‘capital’ (as in, money and valuable assets like real estate, buildings, businesses, etc) tend to see greater returns than those who rely on income (as in, wage labourers), which tends to rise slowly as the economy overall grows. This means that over time – unless specific action is taken to prevent it – the rich keep getting richer. This is expressed in his famous articulation that the returns on capital (r) > (g) growth in the economy. See e.g. Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. See also Saez, Emmanuel, and Gabriel Zucman. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay. New York: WW Norton, 2019.

- We call this process ‘elite overproduction’, namely the process by which the requirements to retain elite status and to secure top positions in government, business, academia, and any other valued sector rises and rises over time as wealth accumulates in the hands of a small – but growing – number of people, yet the number of open positions remains largely static. This is akin to a game of musical chairs, but instead of a chair being removed each turn, new players are added to fight over the same, small number of empty seats.

- Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Edited by Hans-Friedrich Mueller. New York: Modern Library, 2003.

- This isn’t the place to talk about how and why exactly this has been happening, though some of our colleagues have written extensively and persuasively about this critical topic. See for instance: Hickel, Jason. The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions. New York: Random House, 2017; Christiansen, Christian Olaf. “The Mainstreaming of Global Inequality, 1980–2020.” Contributions to the History of Concepts 18, no. 3 (2023): 52–82; Albert, Michael J. Navigating the Polycrisis: Mapping the Futures of Capitalism and the Earth. MIT Press, 2024; Turchin, Peter. End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites and the Path of Political Disintegration. London: Random House, 2023. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/447345/end-times-by-turchin-peter/9780141999296.

- Many of these arguments are described in more detail in: Hoyer et al (forthcoming): Hoyer, Daniel, James S. Bennett, Harvey Whitehouse, Pieter François, Kevin Feeney, Jill Levine, Jenny Reddish, Donagh Davis, and Peter Turchin. “Crises Averted. How A Few Past Societies Found Adaptive Reforms in the Face of Structural- Demographic Crises.” OSF, January 3, 2022. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hyj48.

- It is crucial to acknowledge that these reforms certainly left many groups out, focussing almost entirely on the welfare of white male wage-labourers.