In an era of mounting systemic threats, conventional approaches to risk assessment are proving inadequate. The problem for investors isn't just about better data or smarter models, it's about fundamentally rethinking how risks are identified and managed in an interconnected world. What if the most important intelligence is already inside the building, just not inside the boardroom? Today’s investors need mechanisms that capture insight from those closest to emerging risks.

Boeing as a Governance Warning

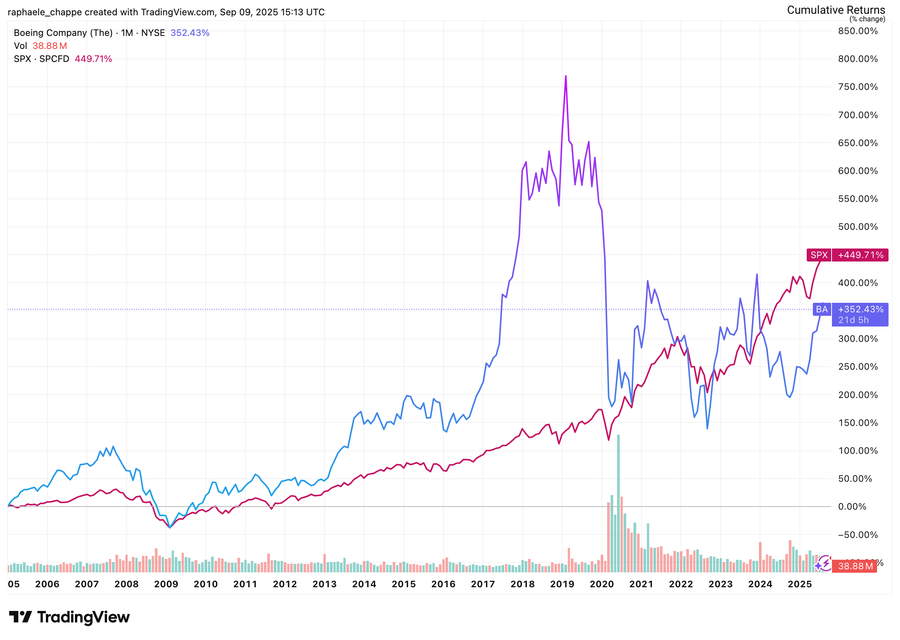

Consider the example of Boeing. A firm can generate record returns right until disaster strikes. Boeing illustrates this problem with chilling clarity. Once synonymous with American engineering excellence, it has become a cautionary tale of systemic failure: two deadly 737 MAX crashes, regulatory breakdowns, criminal investigations, and a collapse of public trust. Yet until 2019, when its share price sharply corrected, Boeing consistently outperformed the S&P 500, even as operational risk accumulated beneath the surface (Fig. 1). As a large-cap index component, Boeing likely benefited from persistent capital inflows, potentially insulating it from market discipline.1

Fig 1. Boeing vs. S&P 500, 2005 – 2025

Source: Trading View

Following its 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas, the company shifted its culture to emphasize financial metrics over engineering excellence. Share buybacks and dividends dwarfed investments in research and development.2 Complex outsourcing introduced supply-chain fragility.3 Executive pay, largely structured around equity-based incentives, created perverse incentives to cut corners, allowing CEOs to reap massive payouts despite safety failures.4

Lessons for Investors

Boeing underscores the limits of relying on boards to manage governance and risk. Directors failed to establish systems to monitor safety-critical issues, despite fiduciary duties to oversee them.5 The board’s homogeneous culture and composition (primarily business and finance backgrounds) reinforced deference to management, with too few members possessing the technical expertise required for a safety-critical industry.6 Whistleblower concerns never even reached the board.

Disclosure frameworks and ESG ratings aim to highlight non-financial risks but often provide only a partial picture.7 Companies can score well on some dimensions while masking deeper cultural and operational risks.8 For investors spread across thousands of holdings, deep due diligence on every firm is infeasible. Without direct insight into operations, investors can miss the risks most material to long-term value (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cracks Beneath the Surface

Source: AI-generated image

Navigating System-Level Risk

The problem extends beyond individual firms. Flawed incentive structures can push managers at systemically important companies to externalize costs that harm workers, communities, and the environment. These spillovers compound into system-level risks that threaten diversified portfolios. Research shows that more than 75 percent of portfolio variability comes from broad market risk—not individual stocks.9

In today’s “polycrisis,” investors face systemic risks that undermine the foundations of financial value, such as climate instability, geopolitical fragmentation, and social unrest (Fig. 3). Inequality is beginning to be recognized as a systemic risk threatening portfolios.10 These risks are nonlinear and interconnected, making them difficult to capture in conventional risk models.

Fig. 3. Inequality and Social Unrest as Systemic Risks

Source: Juan Jardon-Piña / Shutterstock

In principle, investors like pension funds and endowments should be well positioned to address such risks. Their fiduciary duties require focusing on meeting liabilities for beneficiaries decades into the future.11 They have incentives to invest in ways that reduce negative externalities, and some have even begun to explore how they might leverage their influence to curb system‑level risks.12

In practice, however, investment teams are evaluated against short-term benchmarks, usually one to three years, which ignore unpriced externalities. This can drive behavior focused on quick returns, even when it conflicts with the institution’s broader, long-term mandate—reflecting systemic blind spots rather than ill intent, as investors lack tools to integrate systemic risks into models.13

Toward Multi-Stakeholder Governance

If traditional risk management is insufficient, investors may need mechanisms that capture insight from those closest to emerging threats. One approach is polycentric governance, where multiple centers of decision-making collaborate to manage complex challenges.14

Governance models that embed diverse stakeholder perspectives can help companies anticipate risks that markets underprice. As we argued in Getting Ahead of the Curve on Dynamic Materiality, workers, communities, and regulators have proximity to operational realities and can provide early warning signals on overlooked risks.15

Models like worker board representation, stakeholder councils, grievance mechanisms, and codetermination create channels for worker input. Evidence from Germany suggests that labor representation on corporate boards reduces agency costs and enhances governance by contributing direct operational knowledge.16 Codetermined firms show steadier long-term performance, narrower wage gaps, stronger innovation, and neutral to modestly positive impacts on productivity, investment, revenue, and profitability.17

Governance representation should extend beyond labor. In Boeing's case, a consumer or passenger advocate on the board might have provided a crucial counterweight to financial priorities. Since the 737 Max accidents, Boeing has strengthened technical oversight and now includes a retired United Airlines pilot on its board, Stayce Harris.

Giving Risk Management a ReThink

The future of investing will be shaped not only by advances in financial models, but also by an awareness that systemic risks call for broader, systemic approaches. For investors, this means rethinking key dimensions of governance:

- Ensuring diverse board composition and culture that reflects stakeholder interests and includes worker representation

- Replacing performance-based equity for executives with long-vesting restricted shares over extended horizons, and extending this principle to board members’ equity compensation18

- Providing board members with regular trainings to strengthen oversight and domain expertise

- Establishing internal work reporting structures that ensure stakeholder interests are not subordinated to financial considerations

Investors cannot diversify away broken systems. By supporting embedding multi-stakeholder perspectives into governance, investors can proactively detect hidden threats and steer companies—and portfolios—toward resilience.

For more on our work at The Predistribution Initiative, see the website.

--

Thanks for reading The Rethink series. All views expressed are the writer’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of ASRA, its members, or host organization, UN Foundation. Stay connected and keep exploring — discover more Rethink pieces suggested below and under “View” on the Events & News page.

--

Footnotes

1/ The rapid growth of passive investing has sparked debate over whether it weakens or strengthens market efficiency. Evidence is mixed: some studies show it distorts price signals and inflates large-cap stocks, while others suggest it can reduce mispricing by enhancing liquidity and aligning prices with fundamentals. See Vladyslav Sushko and Grant Turner, “The Implications of Passive Investing for Securities Markets,” BIS Quarterly Review (March 2018), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3139242; Valentin Haddad, Paul Huebner, and Erik Loualiche, “How Competitive Is the Stock Market? Theory, Evidence from Portfolios, and Implications for the Rise of Passive Investing,” American Economic Review 115, no. 3 (March 2025): 975–1018, available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20230505; Hao Jiang, Dimitri Vayanos, and Lu Zheng, “Passive Investing and the Rise of Mega-Firms,” forthcoming in Review of Financial Studies, draft available at https://personal.lse.ac.uk/vayanos/Papers/PIRMF_RFSf.pdf; Santiago Guzman, Amir Rezaee, and Andrew Clare, “ETF Adoption and Equity Market Macro-Efficiency,” Journal of Portfolio Management 51, no. 6 (April 2025): 158–174, available at https://www.pm-research.com/content/iijpormgmt/51/6/158

2/ Between 2013 and 2019, Boeing spent $43 billion in stock buybacks but only $23 billion in research and development (R&D). Stock buyback information from Les Leopold, “Did Stock Buybacks Knock the Bolts Out of Boeing?,” Common Dreams (January 23, 2024), available at: https://www.commondreams.org/opinion/boeing-safety-stock-buybacks#:~:text=If%20pressed%20about%20stock%20incentives,the%20money%20for%20those%20repurchases; R&D estimated based on Ycharts data here.

3/ Major cost-cutting initiatives led to the outsourcing of 70% of the design, engineering, and manufacturing (including entire sections of the plane) to 50 strategic partners, resulting in a complex multi-tier supply chain with at least 500 suppliers located in over 10 countries. See Christopher Tang, “The Merger That Brought Boeing Low” Newsweek (February 8, 2024), available at https://www.newsweek.com/merger-that-brought-boeing-low-opinion-1867937#:~:text=However%2C%20a%20significant%20cultural%20shift,savvy%20finance%20and%20marketing%20executives; Christopher Tang, Brian Yeh and Joshua Zimmerman, “Boeing's 787 Dreamliner: A Dream Or A Nightmare?” UCLA Anderson Global Supply Chain blog (May 15, 2013), available at https://blogs.anderson.ucla.edu/global-supply-chain/2013/05/boeings-787-dreamliner-a-dream-or-a-nightmare-by-christopher-tang-based-on-work-with-brian-yeh-pwc-advisory-and-joshua.html.

4/ For example, in 2019, CEO Dennis Muilenburg still exited with $62 million in stock options, pension benefits, and other forms of deferred compensation. William Ebbs, “Boeing’s Disgraced CEO Leaves With Millions in Cruel Irony for MAX Victims,” CCN Business Opinion (September 23, 2020), available at https://www.ccn.com/boeings-disgraced-ceo-leaves-with-millions-in-cruel-irony-for-max-victims/.

5/ Under the Caremark doctrine, directors must implement systems for monitoring risks and cannot consciously ignore red flags that suggest potential misconduct. In the Caremark suit brought by pension funds (including New York State Common Retirement Fund and Colorado’s Fire and Police Members’ Benefit Investment Fund), the Delaware Chancery Court found that Boeing’s board had failed to prioritize safety at the highest level. See the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware’s Memorandum Opinion. It ultimately approved a $237.5 million settlement in 2022.

6/ In 2020, among 13 directors, only four had clear backgrounds in engineering, safety, or technical system management. As noted by the Delaware Chancery Court, many board members had a background in business in finance. See Sandra J. Sucher and Shalene Gupta, “What Corporate Boards Can Learn from Boeing’s Mistakes,” Harvard Business Review (June 2021), available at https://hbr.org/2021/06/what-corporate-boards-can-learn-from-boeings-mistakes. For the full list of directors as of 2020 and their biographies, see William W. George and Amram Migdal, “What Went Wrong with Boeing’s 737 Max?,” Harvard Business School case collection (October 2020) Exhibit 1, available at https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=58358.

7/ A range of disclosure and reporting frameworks require or encourage the reporting of safety, governance, and workforce metrics that supplement traditional financial indicators. Examples include the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Human Capital & Risk Disclosures.

8/ For example, in 2018, the CDP (formerly called the Carbon Disclosure Project), the industry standard for environmental reporting, recognized Boeing with an A– rating for CO2 emissions reduction and transparent reporting. See Boeing’s 2019 Global Environment Report p27.

9/ Jon Lukomnik and James P. Hawley, Moving Beyond Modern Portfolio Theory: Investing That Matters (New York: Routledge, 2021).

10/ Joanne Bauer, Paul Rissman and Silvana Zapata-Ramirez, “The Investor Case for Fighting Inequality,” Oxfam and Rights CoLab (September 6, 2024), available at https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/672d08b2d88b396e31d7fdc0/6789100699752462aa363137_Oxfam%20Rights%20CoLab%20The%20Investor%20Case%20for%20Fighting%20Inequality.pdf.

11/ James Hawley, Keith Johnson, and Ed Waitzer, “Reclaiming Fiduciary Duty Balance,” Rotman International Journal of Pension Management 4, no. 2 (Fall 2011), available at https://iri.hks.harvard.edu/files/iri/files/reclaiming-fiduciary-duty-balance.pdf; Keith Johnson, Susan Gary, and Tiffany Reeves, “Proposed US DoL rules on ESG ignore duty of impartiality,” Top 1000 Funds (February 9, 2022), available at https://www.top1000funds.com/2022/02/proposed-us-dol-rules-on-esg-ignore-duty-of-impartiality/. The International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN), an investor-led network, affirms that “fiduciary responsibility extends beyond the traditional duties of care and loyalty to include considerations of timeframe and systemic risks.” See “ICGN Global Stewardship Principles 2024”, available at https://www.icgn.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/ICGN%20Global%20Stewardship%20Principles%202024.pdf. This also means they should not be maximizing returns for current beneficiaries if it comes at the expense of future beneficiaries, see the work of the Intentional Endowments Network (IEN).

12/ Jon Lukomnik and James P. Hawley, Moving Beyond Modern Portfolio Theory: Investing That Matters (New York: Routledge, 2021). See also the concept of systematic stewardship in Jeffrey N. Gordon, “Systemic Stewardship,” 47 Journal of Corporation Law 627 (2022), available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/3799

13/ See Delilah Rothenberg, Dr. Hubert Danso, Frank Van Gansbeke, “Investing to reconnect financial value with people, nature, and the real economy: An Iterative Blueprint For Capital Markets, Actors, Policymakers, and Regulators,” Earth4All (March 2025), available at https://www.clubofrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Earth4All_Deep_Dive_Rothenberg.pdf, which investigates the strong incentives that investors have for advancing systemic transformation, along with the root causes for why they are not yet pursuing systems change.

14/ Polycentric governance is a concept from institutional economics that describes systems in which multiple centers of decision-making collaborate to manage complex challenges. See Elinor Ostrom, “Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems,” American Economic Review 100, no. 3 (June 2010), available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Faer.100.3.641

15/ Irit Tamir and Sharmeen Contractor, with significant support and input from Delilah Rothenberg, “Getting Ahead of the Curve on Dynamic Materiality: How U.S. investors can foster more inclusive capitalism” Oxfam (March 2024), available at https://www.predistributioninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Getting_Ahead_of_the_Curve_on_Dynamic_Materiality.pdf

16/ Larry Fauver and Michael E. Fuerst, “Does Good Corporate Governance Include Employee Representation? Evidence from German Corporate Boards,” Journal of Financial Economics 82, no. 3 (December 2006): 673–710, available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X06001140?via%3Dihub

17/ Simon Jäger, Shakked Noy, and Benjamin Schoefer, “Codetermination and Power in the Workplace,” Economic Policy Institute (March 23, 2022), available at https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/codetermination-and-power-in-the-workplace/. Studies have documented neutral or small positive impacts on firm performance, including productivity, investment, revenue, and profitability. Simon Jäger, Benjamin Schoefer, and Jörg Heining, “Labor in the Boardroom,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 136, no. 2 (May 2021): 669–725, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa038; Jarkko Harju, Simon Jäger, and Benjamin Schoefer, “Voice at Work,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 28522 (May 2024), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w28522.

18/ For example, the Council of Institutional Investors (CII), which provides corporate governance insights to a membership of asset owners, has suggested shares vesting over a period of at least 5 years, and potentially up to ten years or through retirement. See CII’s Policies on Corporate Governance (March 11, 2025), available at https://www.cii.org/corp_gov_policies.